‘Mad Men 7×14: Person to Person’ Review

“I want to keep things as normal as possible, and you not being here is part of that.”

‘Person to Person’ is Mad Men‘s final hour, and it opens with Don driving as fast as he can through the middle of a blasted wasteland. He’s running for the sake of making distance, drawing out wild trajectories between nowhere and nothing. Later, he tells Sally about the crew that broke the land speed record out on the same salt flats.

Don has spent his life in a state of separation. Even to his children he’s a shadowy figure, someone disconnected from the day to day reality of their lives not just because of run-of-the-mill neglect but because he cultivates distance to preserve his sense of self. When Sally tells him about Betty’s terminal diagnosis it isn’t to make him come home, it’s to ask him to lobby that the boys be left with Henry. Don’s family has grown so used to his absence that it’s part of the fabric of their lives, its maintenance a source of oblique comfort. The realization crushes him, driving him into a suicidal spiral that leads him West to California where he seeks out Stephanie in an attempt to matter to someone, to anyone. He presents himself as a solution to her problems, offering money, heirlooms, approval, everything he can think of to make himself relevant. Stephanie, wrestling with demons of her own, sees Don’s desperation for what it is and takes him with her to a secluded New Age retreat.

Even strangers can sense Don’s otherness. “What does that person make you feel?” asks the peacenik facilitator of a workshop about seeing and interpreting emotion in others. “Find a way, without words, to communicate that feeling.” Don’s partner in the exercise, a sweet old lady in a purple shawl, plants her hands on his chest and shoves him away. Earlier in the episode he sleeps with a woman who tells him everyone in town assumes he’s a spy and a saboteur. “I screwed it all up,” he tells Peggy over the phone in one of the episode’s titular person to person calls, “I took another man’s name and made nothing of it.”

Stephanie abandons Don at the retreat, shamed past endurance by people questioning her absence from her child’s life. Before she goes, though, she lances Don’s beloved “This never happened” speech with tired efficiency. “Oh, Dick,” she says sadly, framed by graceful thorn trees, the sound of the ocean close at hand. “I don’t think you’re right about that.” That quiet doubt is the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Don collapses at the pay phone after giving Peggy a garbled and incomplete confession of his many crimes and failings, and for a while he seems reduced to catatonia. He’s overwhelmed by how little he has to offer the people he loves, the people he desperately wishes to know love him as well.

Elsewhere, smaller stories bring the rest of the ensemble onward into an uncertain future. Roger and Marie are getting married, Joan ditches the adult-sized baby she’s been dating and starts a production company, Pete gives Peggy a cactus, and Peggy and Stan get together in a romantic, if indulgent, phone conversation. Roger’s angry little pirouette as he wraps his hotel blanket around himself after a tiff with Marie would easily clinch the episode’s biggest laugh if it weren’t for Peggy’s repeated use of the word “what?” during Stan’s profession of love. Meredith’s confident send-off is appropriately glib while Sally stepping up to feed her brothers and wash the family’s dishes while Betty smokes away her last days on Earth is achingly poignant. Everyone is moving forward, deciding priorities, connecting and coming apart, but in the end the hour is about Don’s journey.

A passer-by at the pay phone takes Don under her wing and shepherds him to a seminar where the longest sustained speech of Mad Men‘s final episode is delivered by a balding, hapless man named Leonard. It concerns a dream he had about being stored in a refrigerator, about the door opening and closing on a world outside where people laughed and touched and loved each other, about a family that doesn’t look up when he comes through the door. “It’s like no one cares that I’m gone. They should love me. Maybe they do. But I don’t even know what it is. You spend your whole life thinking you’re not getting it, people aren’t giving it to you. then you realize they’re trying, but you don’t even realize what ‘it’ is.” Don embraces the sobbing man, embraces himself and his own formless misery.

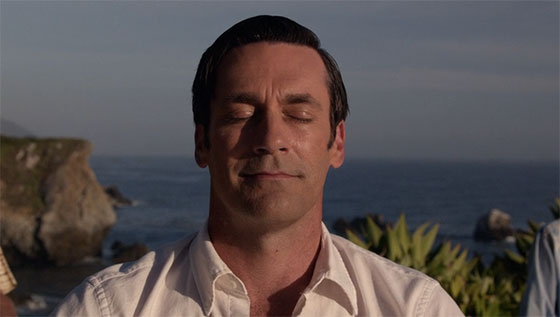

He never goes home. He never gives a rousing pitch or stages a business coup at McCann. He and Roger don’t even speak, having said their goodbyes after their failed attempt to start a branch office way back in ‘The Forecast’. He doesn’t return triumphantly to advertising or become the father his children need and deserve. Diana doesn’t show up. Joan and Peggy don’t go into business. Instead, Don rejects his suffering. He accepts that the billboards screaming “You are okay” from the side of the road are telling the truth, that on the seaward cliffs of California he can salute the sun and find peace through meditation and embracing the New Age.

Like a bubbly guillotine blade, McCann’s real-life “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing” advertisement drops right over Don’s beatific face and reminds us that even love, peace, and togetherness can be sales pitches. Don’s moment of connection to Leonard may have been genuine, but the retreat, in Pete Campbell’s words, is a temporary bandage on a permanent wound. As long as he’s looking for a way out, as long as he believes there’s a magic wand he can wave to take his pain away, Don will never be free.