‘War Machine’ Review (Netflix Original)

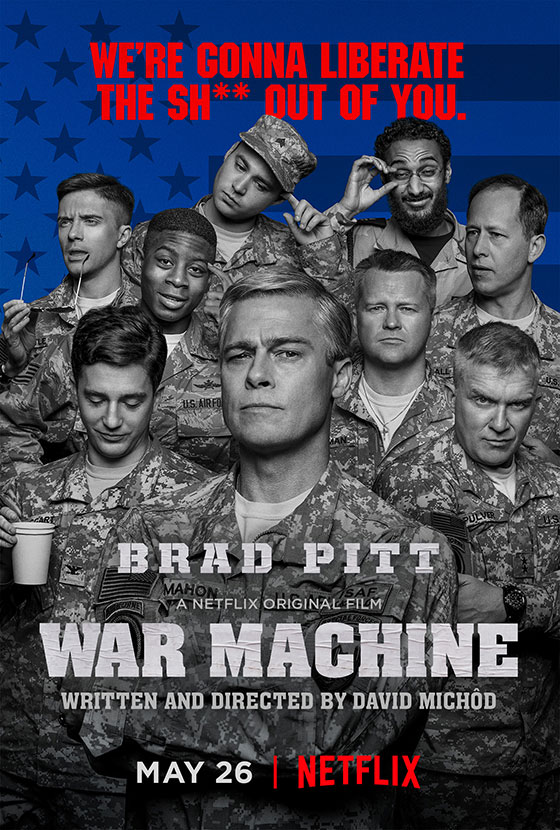

Stars: Brad Pitt, Scoot McNairy, Tilda Swinton, Ben Kingsley, Anthony Hayes, Keith Stanfield, Anthony Michael Hall, Topher Grace, Meg Tilly | Written and Directed by David Michôd

The year is 2010. General Glen McMahon (Brad Pitt) is tasked by a committee of civilian leaders with fixing the mess in Afghanistan. What this actually entails is open to debate. Does it mean winning the hearts and minds of the local populous? Or winning the war against the Taliban? McMahon reckons they’re the same thing.

He and his ego-stroking team take a tour of the country, to see the meagre and underfunded efforts being made by the allies to make good on their promise of roads, schools, democracy, and all that good stuff. McMahon finds a desert of broken dreams.

He requests forty thousand extra troops, so that he might exorcise Helmand Province of its elusive evil. In return he gets minimal reinforcements, and a POTUS intent on pulling out of Afghanistan entirely. Time is running out for McMahon to carry out his glorious liberation.

This is a well-made movie in three distinct acts: the setting of the (very chaotic) scene; the road trip (in which McMahon and his motley crew booze their way across Europe in search of military support); and the delivery of McMahon’s mad master plan in Helmand. The first section is relatively weak, but battle through and you’ll find it hits its stride as the ensemble take their charmless offensive to Paris and beyond.

Written and directed by David Michôd (Animal Kingdom), based on the book The Operators by Michael Hastings, War Machine is an acerbic satire in the vein of Catch-22 or M*A*S*H, with flashes of The Men Who Stare at Goats absurdity. It’s talky and political, but not complicated. Thanks to a rather heavy-handed voiceover, it’s on-the-nose in its condemnation of the theatre it depicts, not to mention its clueless players.

We are meeting McMahon in the twilight of his career; as such, the film struggles to persuade us – beyond a breast full of colours – why he is such a respected leader. Although supposedly based on General Stanley A. McChrystal, Pitt seems to be channelling his twitchy, gurning character from Inglourious Basterds. It’s a performance that delights and aggravates in equal measure: compelling, if tad too broad to really explore the inner conflict at the heart of the man.

And he is a man with heart. The only thing McMahon wants as much as a great legacy is to see the country fixed. If only his ego weren’t smothering his perspective. Although McMahon acknowledges the absurdity of “counterinsurgency” – killing militia whilst simultaneously bonding with their bereaved families – his rampant ambition constantly undermines his own sense of logic, so he fails to see that his goal and his methods are entirely at odds.

McMahon cannot get the troops he desires until the Afghan election is done. But the election is rigged. It’s a frustration to him, and it also encapsulates an essential problem: If McMahon truly cares about democracy for the Afghan people more than personal glory, why is a corrupt election – in which 300 constituents can manufacture 1000 votes – no more than an irritating roadblock on the road to war?

McMahon is let down by everyone because there is no one who can match his ego. His enthusiasm is infectious but ultimately bottlenecked by those above and below him. And that’s before we even consider his insane inability to appreciate reality.

He cannot hear the voices of those around him. He can’t hear the marine (Keith Stanfield) who says that he doesn’t know who his enemy is. And he certainly can’t hear the German politician (Tilda Swinton, almost stealing the movie) who puts it to him that his problem is his “sense of self”. “You can’t build a nation at gunpoint,” points out Sean (Scoot McNairy), a Rolling Stone journalist and our narrator.

This is Pitt’s movie, so naturally the rest of the supporting cast make less of an impact. Do not expect any loveable rogues in McMahon’s gallery. Each is a trumpet for some aspect of their boss’s being, whether it’s the extravagant rage of Greg (Anthony Michael Hall, playing a character based on the now-disgraced Mike Flynn) or PR wrecking ball Matt (Topher Grace). Sir Ben Kingsley has fun playing President Karzai as a reclusive, childish simpleton.

Special mention should go to Meg Tilly, playing Glen’s wife, Jeanie. It’s a beautiful portrayal of a woman who sees her husband 30 days out of the year, and all the strength and fragile pride that go with the life. Playing a professional loner, Tilly is the subtle counterpoint to Pitt’s pantomime, as Jeanie swallows her resentment but cannot conceal her regret.

Nick Cave and Warren Ellis provide the score, and I can’t help wondering if, as McMahon becomes increasingly alienated in his Afghan station, the duo weren’t inspired by the otherworldly musical structures of Brian Eno. It sure sounds like it.

There will be those who will feel uncomfortable with War Machine for its depiction of a campaign mired in hopelessness and incompetence, rather than moral certainty and military triumph. And no doubt there are queues of critics waiting to pounce on Pitt’s deliberately ridiculous performance. But in Pitt’s defence, this is a unique and idiosyncratic character who is on an entirely different wavelength to everyone around him.

It’s all about McMahon, who’s not so much caught between the politicians and the boots on the ground as actively embodying the disconnect between the rhetoric and the reality of war. And to me, that makes War Machine an interesting and laudable work.

War Machine is available on Netflix now.