‘Review 2×06: William Tell, Grant A Wish, Rowboat’ Review

“Try it again. What have you got to lose at this point?”

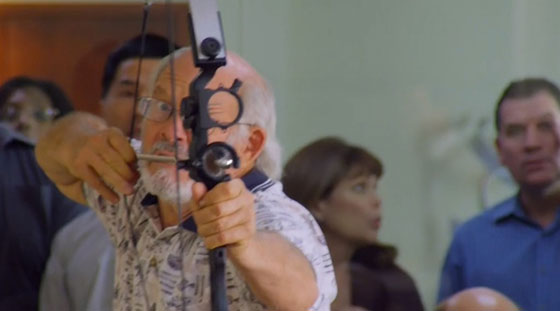

Lucille’s dry words of encouragement toward Forrest’s dad as he shivers and sobs at the prospect of firing yet another arrow at his whey-faced son, already pincushioned with two, might as well be the tagline for the show’s promotional campaign. Forrest has left so much in flames behind him that an arrow through his heart might as well be nothing, just another gory accident in a long chain of misery and heartbreak stretching all the way back to ‘Stealing, Addiction, Prom.’ Forrest’s father queasily tells his son that he loves him, and then he looses an arrow through a plate-glass window and shoots Lucille in the chest.

Forrest’s uneasy expression and shouts of fear and loss as he fires arrow after arrow into a dummy of his son in an attempt to “become a master archer” in three days are contrasted beautifully with Josh and Tina’s sycophantic cheers. “Well how many sons do you have?” Tina asks Forrest when he explains that, his increasing skill notwithstanding, he’d have killed Eric five times over during his preparatory target test. He considers adopting excess sons to buy up more chances at making his big shot and his self-loathing during an exchange with the adoption agent that reads like a very weird serial killer’s shopping list is so palpable it’s almost impossible to watch. Forrest abandons the idea of wagering his son’s life on a roll of the dice and instead hits upon the brilliant idea of foisting responsibility onto his own father. It’s another of the mute, unselfaware stabs at self-annihilation to which Forrest has defaulted throughout season 2’s run. He wants to die, to give up his burdens and wriggle out at last from under the horrible things he’s done in the name of his idiotic show, but asking for it would mean admitting that it’s all been for nothing.

‘William Tell, Grant A Wish, Rowboat’ adopts a simple triptych format in which Forrest’s body, heart, and soul are assaulted and mauled in rapid succession. After the physical ordeal of being shot full of arrows, Forrest is confronted with the fact that his estranged son’s dearest wish is to move with his mother into the home of Joe Dale, Jr., the man who helped Forrest catfish Suzanne. Joe, it transpires, has pursued a connection to Suzanne in the wake of his and Forrest’s fraud. Forrest greets him through gritted teeth, unsubtly calling him a “two-faced monster” before conspiring to help Joe and Suzanne move in together. Tuning into Review is so often the act of watching as a man stab himself repeatedly while refusing to admit he’s in pain, and watching Forrest rip out his own heart out while wearing the absurd blinking light sport coat from ‘Life of the Party’ is enough to bring even real cynics to the crumbling cliff edge of cringe comedy.

The final challenge is oblivion itself. Forrest, drugged and desolate, falls asleep in the rowboat he’s assigned to enjoy alone time in and drifts out to sea, losing his oars in the process. He wakes up with a bad sunburn and a case of the jitters, panicking in the moments before his camera dies, the sea an empty, whispering wasteland all around him. It turns out, though, that there simply isn’t anything that can stop Forrest MacNeil. Not gunfire, not arrows, not accidents in commercial space shuttles, and not the profound spiritual emptiness of spending 94 days lost at sea in a rowboat. The camera fuzzes back in on Forrest adrift in the Pacific trash vortex, his clothes tattered and salt-stained, his skin peeling, his hair and beard a wild mane. “I have been killing and eating the seabirds that perch on top of the garbage,” he cackles, “I’ve been strangling them and snapping their necks with my hands.”

There is no depth from which Forrest cannot escape. He has become the birds he stalks and devours in his floating landfill of an Eden, a direct beneficiary of the worst and most self-destructive of human behaviors. “If you don’t dispose properly of your garbage,” he says after his return, unhinged but unharmed, “you saved my life.” The island is a metaphor for the people who live vicariously through him, for the emotional and spiritual garbage that secretes review by review in the hollow space where his soul once was. This is damn fine television.